The Allan Gray Entrepreneurship Challenge: 2025 Informal Game Winner

Barry Joseph:

So let’s dive in and talk about the winner you all selected for the 2025 Gee! Award for Informal Learning Game: The Allan Gray Entrepreneurship Challenge. What exactly is it?

Chris Baker:

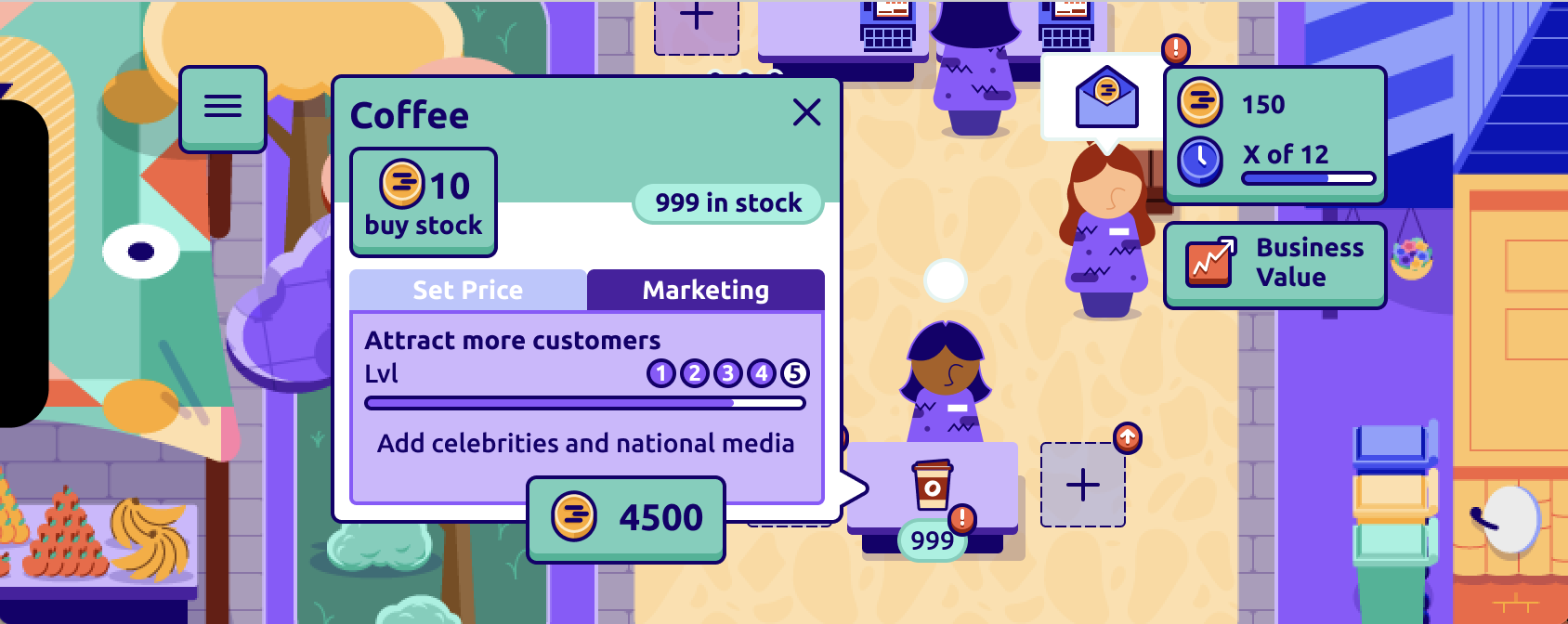

Essentially, it’s an entrepreneurship simulator where players run a burgeoning restaurant business — starting small with a quaint stall, and eventually growing to more robust enterprises like, say, a food truck. You manage pricing, staffing, training, marketing… and react to real-world-like challenges, like natural disasters, community trends, and local awards. Think Dave the Diver meets business ed. What hooked me was the gameplay feedback loop — you really feel like, “I know I can figure this out if I just tweak my plan a bit.” Very satisfying.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

What got me was the reputation system — your decisions affect not just your bottom line, but how employees and customers see your business. It felt ethical and strategic at once.

Brendon Trombley:

The staff dynamics were deep. I had one high-cost employee who seemed always unhappy no matter what — I was planning to fire them, but then the game ended first. That sort of decision-making? Felt real.

Barry Joseph:

Chris, you wrote an excellent summary of James Paul Gee’s “Intro to the 13 Principles of Good Learning Games”. Can you please take us through them, one by one and, together, explore how each played out?

Chris Baker:

You got it! We’ll start with the Agency Principle: “Good learning requires that the learner feels like what they do matters. They must be active agents in their learning. Their decisions and actions must visibly affect outcomes.”

This game lives or dies by that idea. The feedback loop is quick and visible — you change prices or staffing, and it matters; you “feel” it in game.

Brendon Trombley:

Totally. I had so much control over every aspect of the business. And every choice fed directly into what happened next.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

Same. Whether I failed or succeeded, it all felt tied to my choices.

Chris Baker:

And that’s what made it feel effective; you weren’t passively watching things play out, and your choices had immediate effects.

Next, we’ll take a look at the Customization Principle: “Learners should be able to solve problems in ways that match their style. Good learning games adapt to player preferences and invite new strategies.”

I played twice: once trying expensive items at low prices (which failed), and then again with a single mid-tier item — which performed much better. The game rewarded my adapted strategy.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

My chicken-wing-only, full-marketing run? Totally different, but it worked. The game supported all kinds of play.

Brendon Trombley:

My first run accidentally excluded marketing. Still made it through — and tried new approaches in later playthroughs.

Chris Baker:

It’d be even stronger with features like avatar customization or naming your restaurant. But, still, what’s there already supports multiple paths to success.

Third, we have the Identity Principle: “Learning starts when you know who you are in the learning space. Good games help you connect the learning to your sense of self.”

The game anchors you in a community — you’re not a faceless CEO, but a local business owner with roots and responsibilities.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

As a Black woman, I felt seen. The cousin giving you seed money? That’s my lived experience. It helped me imagine myself as an entrepreneur.

Brendon Trombley:

You’re not managing from above — your character is also in the kitchen, hustling alongside the employees. That made me feel real ownership of the business.

Chris Baker:

Right — and the community dilemmas that emerged reinforced that identity. You weren’t just running a business; you were part of a world.

Next, we have the Manipulation Principle: “Learning deepens when you can finely control the world or your character. That granular manipulation helps create embodiment in the learning space.”

This game is full of “dials” — prices to fine-tune, wages to alter, employee training to pursue, inventory to acquire, etc. You have to tweak things constantly to respond to your situation.

Brendon Trombley:

Every lever had a visible consequence. If something went wrong, I could trace it to a decision.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

And the game encourages trial and error. I’d mess something up, tweak, and try again.

Chris Baker:

Exactly — mistakes became learning moments. You don’t just observe the system; you shape it.

Fifth, we’ll discuss the Sequencing Principle: “Good learning games scaffold challenges. Early tasks prepare you for harder ones, building mastery step by step.”

This game gives you a fast tutorial, then lets you loose. It doesn’t hold your hand; it’s “sink or swim” just like real entrepreneurship. Overall, it was effective.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

It’s quick to teach the basics. Then you're experimenting, learning through doing.

Brendon Trombley:

And you choose when to scale up — add staff, diversify your menu. The pacing is in your hands.

Chris Baker:

It walks that fine line between clarity and freedom. You feel prepared, but challenged.

This next one’s my personal favorite: the Pleasantly Frustrating Principle: “Learning is at its best when it’s ‘pleasantly frustrating’ — right on the edge of your abilities, pushing you without overwhelming you.”

I was hooked. Failing wasn’t discouraging — it made me want to try again. That’s gold!

Brendon Trombley:

Exactly. I’d think, “One more try — I know I can get it right next time.”

Ashlyn Sparrow:

I was shouting at the screen — but also diving back in. The frustration felt productive.

Chris Baker:

That feeling of “I’ve almost got it; I can do this.” That’s flow. The game nailed it.

Next, the Cycle of Expertise Principle: “You master a skill, apply it until it becomes second nature, then face a challenge that forces you to rethink your strategy. This cycle builds deep expertise.”

I went from struggling with something simple like dialing in my chicken wing pricing… to eventually juggling multiple staff, adjusting costs on the fly, and employing marketing to promote my business. I could feel myself “leveling up”.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

My comfort with basic mechanics let me focus on bigger decisions later.

Brendon Trombley:

And each new playthrough built on the last. The sense of growth was real.

Chris Baker:

The eighth principle is Just-in-time & On-demand: “In a well-designed game, ‘Just-in-time’ learning gives info when you need it. ‘On-demand’ learning allows you to seek more out when you feel ready. Together, they create responsive learning environments.

This game definitely did just-in-time learning really well, but I’d love to see more on-demand tools — like a business glossary or codex.

Brendon Trombley:

Same. I understood when to do things, but not always why. I wanted deeper insight.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

Especially with marketing. I knew I should do it, but not what strategies worked best.

Chris Baker:

Adding a “knowledge vault” would elevate the learning experience for those who are ready to learn more at a more rapid pace.

Our next principle is the Fish Tank principle: “Metaphorical ‘fish tanks’ are simplified systems that let you study how parts interact before exploring the bigger picture. They're digestible models of complex realities. You don’t study the ocean all at once; first, you start learning with a fish tank!”

And this game is a great “fish tank”. You’re not running a multinational corporation at the outset; you’re managing one simple stall. But you still get to juggle hiring, pricing, customer feedback, and community impact — the fundamentals of business.

Brendon Trombley:

Even the UI supported that — it all happens in one visual space, like watching a tank.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

I got to test cause and effect in a manageable world. Felt focused, not overwhelming.

Chris Baker:

Next, the Sandbox principle: “A ‘sandbox’ is a safe space for experimentation. It encourages play, risk-taking, and learning through failure.”

It’s not a sandbox in the traditional Minecraft sense — but you do get the space to try things, mess up, and try again. The game doesn’t punish; it teaches.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

I could run risky experiments without fear. Even failing was part of the fun.

Brendon Trombley:

The boundaries are fixed, but the freedom inside them is real.

Chris Baker:

It’s more of a simulation, and not a sandbox — but it encourages the same spirit of play.

Now for our eleventh principle, Skills Under Strategies: “Learners master skills best when they’re embedded in larger strategies. The “why” makes the “how” worth learning.”

Skills like budgeting, resource planning, and pricing are well integrated. Some soft skills — like conflict resolution — are a bit oversimplified, but that’s an understandable tradeoff for gameplay accessibility.

Brendon Trombley:

Right. Managing staff is a click, not a conversation. But budgeting? Super real.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

The meaningful context kept the skills engaging. I wasn’t just learning—I was applying.

Chris Baker:

Next we’ll take a look at Systems / Model-Based Thinking: “Games that encourage players to build mental models teach complex reasoning. You understand how systems work — and how your actions ripple through them.”

Every action affects another part of the system. Raise wages? Staff morale improves — but costs rise simultaneously. Cut prices? You sell more, sure — but might run out of food. It’s a delicate balance.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

I started thinking like a business owner. Everything connected—marketing, staffing, customer flow.

Brendon Trombley:

And the social systems mattered too — not just profits. The game captures a more full ecosystem of entrepreneurship than many other tycoon type games.

Chris Baker:

Finally, we’ll end with the Meaning as Action (Situated Meaning) Principle: “True understanding happens when words and symbols connect to actions and experiences.”

This game shines at providing “experiences” — but it could do more to tie those to “language”. Terms like “profit margin” show up, but I wanted clearer links between the actions I took, what terms those actions related to, and why said terms ought to matter to the player.

Brendon Trombley:

Exactly. I experienced the concept, but I wasn’t always delivered the name for it.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

Sometimes it forced meaning — like making you say no to donations even if you had some gold. More nuance would make it richer.

Chris Baker:

Agreed. It’s strong, but more explicit connections between gameplay and terminology could help make the learning even deeper.

Barry Joseph:

In one sentence—why does this game deserve recognition as best in its class?

Brendon Trombley:

It’s genuinely fun and deeply educational — without compromising either.

Ashlyn Sparrow:

You’d play it for fun and walk away smarter. That’s rare.

Chris Baker:

Exactly; it’s not “chocolate-covered broccoli”; it’s good on its own and also intentionally “nourishes”. Not that I don’t like broccoli, hah. The Allan Gray Entrepreneurship Challenge is an excellent model for informal learning games!

Thanks to category lead, Barry Joseph (Barry Joseph Consulting), and judges: Chris Baker (WI Department of Public Instruction), Ashlyn Sparrow (Senior Research Associate, Weston Game Lab, Media Arts, Data, and Design Center, University of Chicago), and Brendon Trombley (Games for Change).